← Back

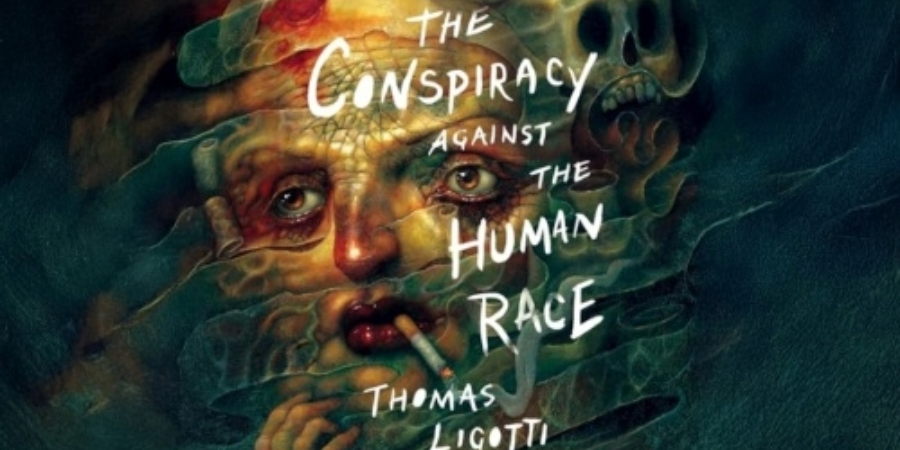

The Uncanny Mister Ligotti (Part 3 - Finale)

Section 5: The Cult of Grinning Martyrs

One imagines, in reading this section, that Mister Ligotti has faced widespread criticism for his pessimistic views. He derides society’s misconception that pessimism is merely psychological melancholia—a mere chemical imbalance of the brain—or worse, a desire to be contrarian. He argues that humanity pathologically clings to the unfounded truth that there is “some reason for the continuance of the human species.” Anyone who says overwise risks being socially exiled. “Keep your powder dry and your pessimistic, nihilistic, and defeatist temperaments in check,” seems to be the motto of the life-affirming crowd. But Ligotti does not feel compelled to kowtow to social mores, and he thinks poorly of those who do.

The discussion does not become easier when one considers the ethical implication of having children. Ligotti maintains an anti-natalist view that bearing offspring into a world of suffering—with only the surety of death before them—is a lamentable horror. Such actions should be robustly criticized, or at least self-examined by would-be parents, he writes. Our biological imperatives can be set aside in this argument, because we are hyper-conscious creations capable of reflection before copulation. If we are to be cursed by consciousness, he argues, then we had best use our wits to curb our most harmful impulse of propagating human suffering.

What drives us to want children, in Ligotti’s summation, are a variety of selfish incentives: to extend our own legacies; to win the esteem of our neighbors; to ensure our own caretaking; to fill our humdrum lives with entertainment; or to bandy about our genes as “…consumer goods, trinkets or tie-clips, personal accessories to be worn about town.” Should we not give equal thought to the idea that our children are given no choice in being born; that they may suffer from physical and psychological disease; and that they will inevitably taste the horror of death? Ligotti’s opinion on the matter is that we should all have more opinions on the matter (of procreation). We should not simply be swept along by social contrivances, and thus continue propagating the conspiracy against the human race.

As a side note, I found it interesting that Ligotti does not castigate reproduction in its entirety. Here, oddly, he softens his tone, claiming that there are far worse transgressions than bearing children. One wonders if perhaps he did, ultimately, kowtow to public pressure in his own way, mindful of how anti-natalism would be viewed by his readers. (See footnote “Anti-Natalist Caveat”, 3).

Section 6: Autopsy on a Puppet: An Anatomy of the Supernatural

At last, horror literary fans, rejoice! Ligotti devotes this final section of his book to the sublimation of horror. In exploring the plot, themes, and characters of famous works of the macabre, Ligotti argues that there is a deeper truth to be found behind the fantastical curtain of fiction. Literary horror is not merely escapism, he argues. It is an imperfect mirror into the Uncanny. This is the quintessential essence of horror as art. It must mimic Life—which is to say, it must be filled with uncanniness, dreadfulness, and inevitable death. As such, Ligotti derides any horror tale with a happy ending. Such stories are false betrayals of our natural intuition, our understanding that death alone awaits the awakened consciousness.

Among the works included in his reflections are Poe’s The House of Usher, Blatty’s The Exorcist, Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness, Shakespeare’s Macbeth, as well as more obscure short story titles. In particular, Ligotti speaks glowingly of Lovecraft’s emphasize on ineffable Horror as the central theme of his tales, relegating characters to mere tools of perspective. Such writing speaks to Ligotti’s core belief that we are but witnesses to the cosmic spectacle of death. Once Nature latches its bloody jaws about our throat, there is naught to do but surrender, as many of Lovecraft’s hapless heroes do. In this regard, Ligotti maintains that Lovecraft wrote like a progressive visionary. “As a fiction writer, [Lovecraft] will ever be the contemporary of each new generation of mortals, because there will always be many a character in the real world for whom life is unacceptable.”

Lovecraft, like so many other pessimists, understood that “Behind the scenes of life, there is something pernicious that makes a nightmare of our world.” In horror literature, this nebulous Something takes the form of the supernatural. But the supernatural must be more than superstition, Ligotti writes. In reality, it is our sense of the supernatural—or the uncanny—that engenders our true horror. That feeling comes from contemplation of Death, the unthinkable specter that looms large in our shadow like the annihilating gods of Lovecraft’s swirling cosmos. Our sense of terror comes the feeling that we are merely puppets on a string, granted just enough consciousness to understand that we are trapped in a house of horrors where no one gets out alive.

There is only one question we must ask ourselves about Death, and it is the focal question that horror writers must contend with.

Not When, but How?

Conclusion

Ligotti’s overarching thesis, if one could be drawn, is that we are living in a meaningless nightmare, and to think otherwise is to succumb to self-delusion. Some readers, no doubt, will find this book unsatisfying, in that Ligotti offers no lifeline to crawl back from the abyss. But Ligotti would scorn the very existence of a "lifeline" and berate us into believing that we should not want to be rescued from reality. If anything, he seems to bid us to let go of the ledge.

To be fair, no one should be fooled into thinking this is a self-help book. Rather, this treatise should be viewed as an awakening of consciousness, a stirring from the long nightmare of self-delusional gimmicks. The book’s title invites us to see the world as a conspiracy meant to keep humans docile and happy, smothering our terror of existence. In tongue-in-cheek fashion, Ligotti takes his title from a reference in his own short story, “The Shadow, The Darkness,” where a character stumbles upon a book of forbidden knowledge (“…[A book] based on the nonexistence, the imaginary nature, of everything we believe ourselves to be.”) He implies that forbidden knowledge is only forbidden by our own reluctance.

Many of us lack the mental fortitude to follow Mister Ligotti into the dark abyss. We cringe at the thought of wallowing in pessimism until the end of our days. But even those of us clinging to terra firma will be left with an unshakable discomfort that we have seen things that cannot be unseen, and have read things that cannot be unread. Nihilism infects the mind like a germ, and Ligotti's writing is a persistent infection of our most sacred faculties.

In the end, I am left to wonder which would be the greater nightmare for our society—to collectively embrace the horror of our existence, or to let it devour us, one by one, when our final day comes?

End

*

Post a comment