← Back

The Uncanny Mister Ligotti - Part 1

Warning: Readers who suffer from depression, or have experienced suicidal thoughts, should proceed with caution. There are heavy topics of conversation below, including the meaning (or meaninglessness) of human life.

Introduction

I’ve often joked that if you stare long enough into the abyss, Thomas Ligotti stares back at you. There’s a uniquely pessimistic vein to Ligotti’s writing that stands out in the pantheon of horror. His stories are filled with the hopelessness one expects from great “cosmic horror”— those Lovecraftian principles of existential dread, unrelenting darkness, and moral ambiguity that strangles the ego, leaving us weeping in terror as we awaken to the incongruous festival of death.

Ligotti is indisputably a master of fictional horror. His stories are frightening and Kafkaesque, exploring the boundaries of the “uncanny.” His most famous works include Songs of a Dead Dreamer (1991), The Nightmare Factory (1996), and My Work is Not Yet Done (2001), which have won widespread acclaim and fostered a devoted international following.

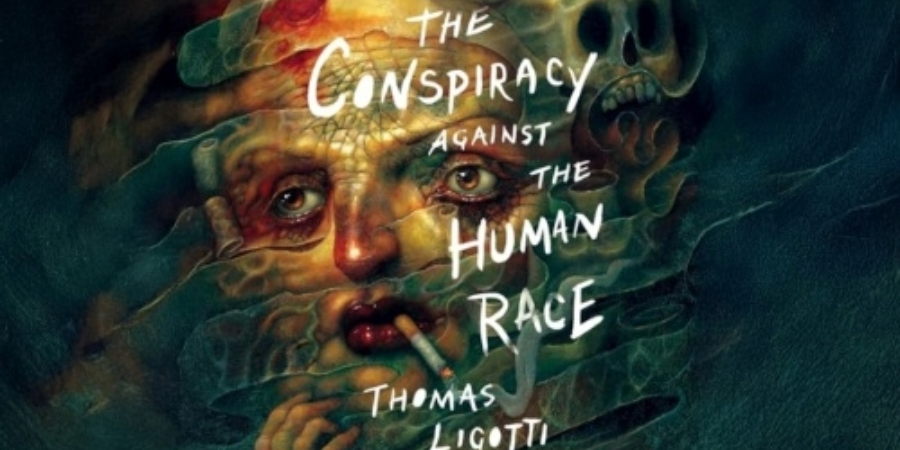

In these reflections, though, I set aside the world of fiction and turn my attention to a singular work of nonfiction by Mister Ligotti, entitled “The Conspiracy Against the Human Race.” As best I can tell, this is the author’s most serious attempt to detail his convictions as a horror writer and philosopher. Anyone with a curiosity about existentialism, or an unshakeable sense of the Uncanny, will find this work equally illuminating and dreadful.

In this essay collection, Ligotti gives voice to a deeply pessimistic worldview that posits that Life as a diseased and undesirable state of being. Consciousness is not a gift, but rather “the parent of all horrors,” as Ligotti puts it. The ideas put forth in this book are harrowing and fearless—to say nothing of Ligotti's penchant for a deliciously macabre turn-of-phrase.

I imagine many readers will find this book far more disturbing than anything they've encountered on the fiction aisles. As a work of nihilist philosophy, the book unapologetically argues that we are better off to never have existed. If you find this idea offensive, consider yourself warned before reading on.

With that being said, the following reflection offers only my interpretation of Ligotti’s grand nightmare. I am not a philosopher, nor a scholar of Mister Ligotti’s corpus of work. My impressions are limited to the pages of this book alone. I ask only that you bear in mind that all philosophy is subjective. I encourage you to read the book yourself and draw your own conclusions.

Section 1: The Nightmare of Being

In this opening chapter, Ligotti divides philosophers (and humanity at large) into the opposing camps of “pessimists” and “optimists.” This dichotomy serves as the foundation for the rest of the book. Ligotti argues that the world is predominantly filled with optimists—those who choose to believe that life, and their fortunes herein, are forever improving, and who abide by the mantra that “Day by day, in every way, I am getting better.” Ligotti derides this adage as childishly naïve and bids us to consider the alternative: that we are not getting better, and that we were never well to begin with.

Life did not evolve with human bliss in mind, Ligotti argues. "...To be alive is inhabit a nightmare without hope of awakening to a natural world, to have our bodies embedded neck-deep in the quagmire of dread, to live as shut-ins in a house of horrors in which nobody gets out alive." Evolution is a brutal bloodsport, a “festival of massacre” in which the only constant among all living things is the certainty of death—and a great deal of suffering along the way. Those who have evolved with self-awareness see themselves wrongfully as spectators to this festival. In truth, we are its participants and its inevitable victims. To ignore our impending demise is akin to allowing the hatchet murderer into our home--to live among us, murdering at will, while we totter along with our daily amusements.

As opposed to the optimists, the pessimists see the world clearly as it is—which is to say, as Mister Ligotti sees it. Ligotti posits that death is the only certain principle in life, and any other moral or existential frameworks we spin up are delusions of our own mind. There is no greater meaning to our lives than the capricious speck of existence allotted to us by Nature. Nothing matters while we live, and certainly nothing will matter when we’re dead. Therefore, the question we must ask is not, “Why do I exist?” but rather, “Why should I exist?”

A pessimist would argue that human consciousness is an exquisite misery which, day by day, forces us to contend with our impending death. We may choose to distract ourselves with life’s pleasures and religious mantras—but all of these are self-delusions. A pessimist holds that there is no solution from the unbearable suffering of human consciousness, except through death. Taken to its conclusion, a true pessimist would argue that the only escape from the nightmare of existence is extermination of human consciousness.

I should note here that Ligotti anticipates—and pushes back vociferously—against the argument of suicide as a means to an end. He notes that this is a false petard upon which critics seek to hoist the pessimists, claiming hypocrisy from Life-Negators who choose to go on living. To simply note the benefit of nonexistence, Ligotti argues, is not the same as advocating for suicide (See Footnote 1, "On Suicide).

Yet, if Ligotti draws a line at individual self-murder, he seems sympathetic to the idea of “phasing out” humanity by other means. Specifically, through the act of limiting procreation, we can bottleneck ourselves into painless nonexistence. This may sound like a more humane and palatable argument than calling for death camps or mass suicides. But one is left puzzling out Ligotti's moral distinction in the end game.

Equally strangely, Ligotti does not extend the same compassion toward “Nature,” whom he holds accountable for the evolutionary blight of human consciousness. He brooks no argument about exterminating humanity to “save the planet.” “Nature produced us,” he writes, “or at least subsidized our evolution. It intruded on an inorganic wasteland and set up shop. What evolved was a global workhouse where nothing is ever at rest, where the generation and discarding of life incessantly goes on. By what virtue, then, is [Nature] entitled to receive a pardon for this original sin…?” His extends this train of thought to a surprisingly vehement conclusion: “Once we settle off ourselves off-world, we can blow up this planet from outer space. It’s the only way to be sure its stench will not follow us. Let [Nature] save itself if it can.” On this singular issue, Ligotti strays from the measured tone of the rest of his book, carving out a moral paradigm I found difficult to follow.

Ligotti understands the most of us have little desire to share in the company of pessimists. But this is not a matter of choice, he argues. To exist free of pessimist thought is to repress our obvious horror of existence with a variety of self-delusions. “In plain language,” Ligotti writes, “we cannot live except as self-deceivers who must lie to ourselves about ourselves, as well as about our unwinnable situation in the world.”

How do we achieve such self-deception? Here Ligotti quotes the pessimist Peter Zapffe, who lays out four techniques in his 1933 essay, The Last Messiah. First, we compartmentalize negative thoughts into the back of our minds. Second, we anchor our sense of purpose to institutions like religion, country. Third, we fill our daily lives with constant distractions, such as politics, news, and gossip, to stave off thoughts of death. Finally, we sublimate our horror into more palatable forms of art and expression—including books like this one.

From time to time, Ligotti notes that we wizen up to these gimmicks and catch a glimpse of the horrible puppeteer jerking at our strings. We awaken to the horror of existence. Then our nature compels us to find another blissful potion to imbibe. In Ligotti’s words:

Once the facts that repressional mechanisms hide are accessed, they must be excised from our memory—or new repressional mechanisms must replace the old—so that we may continue to be protected in our cocoon of lies. If this is not done, we will be whimpering miseries morning, noon, and night, instead of chanting that day by day, in every way, we are getting better.

*

End of Part 1

*

0 Comments Add a Comment?